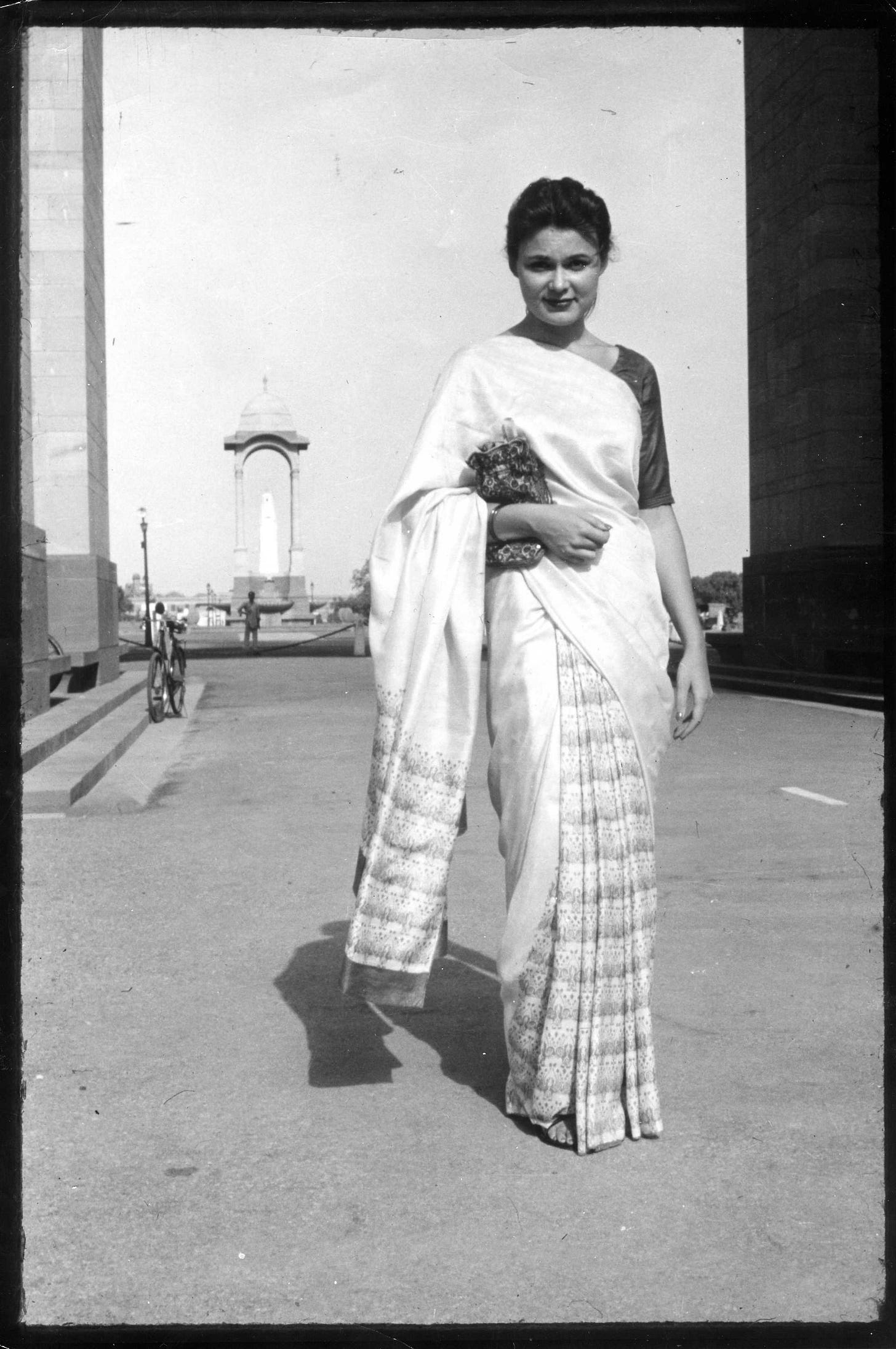

When I reflect on the importance of India in my life, I think most of all of sitting on a New Delhi veranda in the 1970s, drinking tea with Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, whose first name was (and is) enough to identify her in many countries of the world. Biographical dictionaries list her as “freedom fighter, social worker, writer.” In the 1950s, when I first met her, she was also in her fifties and already a legend for her leading role in the Freedom Struggle with Gandhi and Nehru-an activism for which she spent five years in British jails — and for her pioneering of the Indian handicraft movement. Our meeting was arranged by my oldest friend in India, Devaki Jain, because we wanted to ask Kamaladevi’s advice. Since Gandhi’s nonviolent tactics were so well suited to women’s movements around the world, we were thinking of studying his letters and writings, distilling what was most useful, and creating a kind of Gandhian/feminist handbook.

Kamaladevi listened patiently. Only at the end did she say, “Of course Gandhi’s tactics were suited to women — that’s where he learned them.” It was a sudden understanding that made us all laugh; one more instance of history lost, and then being attracted to what once was ours.

When I returned home, I lost track of Kamaladevi. I knew only that she had continued to travel the world into her eighties, helping other countries to preserve their creativity and culture in a handicraft industry, too, and also writing many books. But I always remembered this woman who taught us women’s history over a cup of tea, while continuing to make history herself.

She died at the age of eighty-five on her way to make a speech, effective to the last. Devaki Jain wrote a moving tribute: “I weep for her absence — a central support for realistic idealism… She made museums appear like bread or water — things without which one could not live.” She described how Kamaladevi, asked to join dignitaries on a podium and light a lamp celebrating the golden jubilee of the All India Women’s Conference, had said, just a year before she died, “I have never gone on to a raised platform, it connotes hierarchy.” As Devaki explained, “She lit the lamp at the back of the hall, to the delight of the last rows.”

This piece is excerpted from the essay ‘Doing Sixty’ in Gloria Steinem’s 1995 book Moving Beyond Words. It has been edited for clarity.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful article on your meeting with Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay , I have been a great admirer of hers and treasure her knowledge and book of Indian textiles & handicrafts that I was gifted many years ago and became my Bible of sorts .

It was great to know that two legends from distant continents connected and were influenced by each other . Both of whom I admire greatly 🙏🙏

I wonder if VP Kamala Harris was named after Kamaladevi? Her middle name is Devi and her family has such deep activist roots in India.